Trauma has always been a significant concern in schools, but it has only intensified in the wake of the pandemic and increasing school violence. School districts currently face unprecedented challenges for the well-being, safety, and academic success of their students and staff, as well as mounting academic and social gaps for students, according to LindaGail Walker, Executive Director of Innovation & Impact at MeTEOR Education, during a talk at the K-12 Facilities Forum.

What is Trauma?

Trauma can change one's life in an instant, and its effects can last for years. We’ve all seen the effects of the pandemic on both kids and adults — and maybe even ourselves.

“How many of you are noticing your campus people have shorter fuses? How many of you recognize that at your campus you might have a shorter fuse?” asked Walker.

Trauma creates a crisis of confidence — individuals no longer trust that a government system is functioning properly, so they no longer support it. Distrust is an automatic response, and one that has been important for human survival, but in today’s social and political environment it is arguably doing more harm than good.

When distress and distrust escalate, the only way to alleviate it is through transparency. But the damage is often already done. People enter into a "survival brain" state that inhibits deep learning, retention, and reflection.

What Causes Trauma in Children?

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are experiences of abuse, neglect, household dysfunction, mental illness, domestic abuse, divorce, separation, incarcerated relatives, and substance abuse. Walker told the audience that while people like to think of students as happy and excited to learn, many are dealing with problems we might never dream of.

“What we do right now in our schools matters for our kids. We cannot completely overcome their ACEs, but the interventions we do with them will make a difference and it makes a difference in their lives.”

Long-term consequences of ACEs can escalate from social, emotional, and cognitive impairment, to the adoption of health risk behaviors, to disease, disability, and social problems, and eventually, to early death — statistics show that children with six or more ACEs died 20 years earlier than those without.

It is essential to redefine safety and wellness, as it is about more than just the hardening of schools. Safety and wellness are about creating social, emotional, intellectual, and physical safety for students and staff from the inside out.

The most recognizable impacts of trauma on education fall into two intertwining categories. The first is academic performance, resulting in reduced cognitive capacity, sleep disturbances, difficulties with memory, and language delays.

The second is social relationships, causing a need for control, attachment difficulties, poor peer relationships, and unstable living situations.

ProSocial vs. Antisocial Behaviors

Walker asked what kind of community the audience would want to build — prosocial or antisocial. While we may use the term “antisocial” loosely in casual conversation, its definition includes:

- Any acts that harm or negatively impact another individual

- Threats, bullying, discrimination, deceit, and lack of remorse

- Acts that lessen secure & cooperative relationships

In contrast, “prosocial” behaviors are defined as any act that benefits another individual, such as sharing, donating, being friendly, expressing concern, and other helpful conduct.

Promotion of positive interactions and behaviors can be as easy as being kind, sharing, helping, empathizing, comforting, encouraging, being generous, complimenting, collaborating, teaching one another, and teamwork. They often have a greater impact than negative behaviors and aggression.

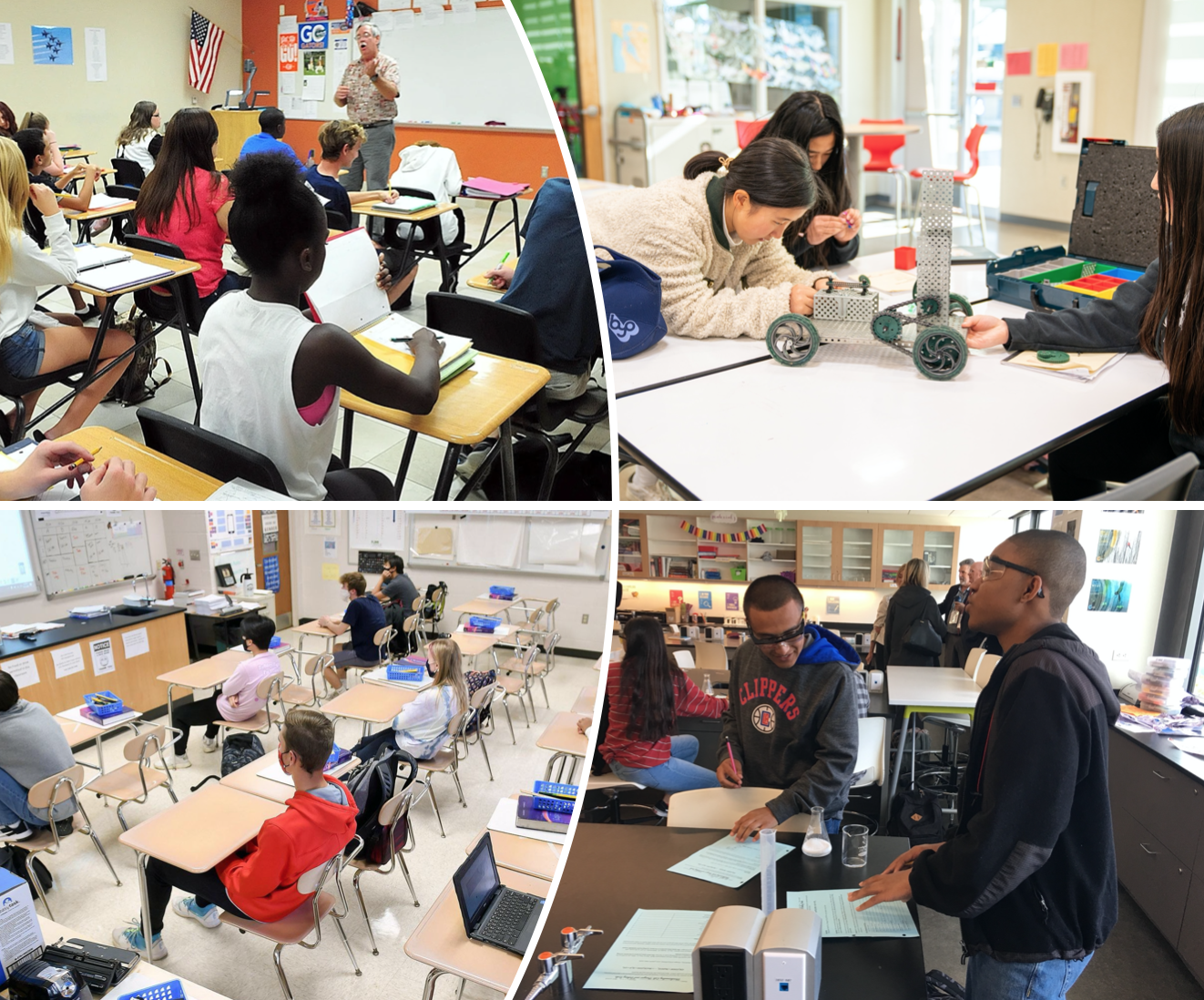

Walker emphasized how important collaboration also is, and challenged K-12 leaders to observe whether students are really interacting or just sitting together. If they aren’t interacting, one thing that might be missing is the feeling of being in a safe space.

Building ProSocial Learning Ecosystems

Building design should embrace that concept and help create a safe harbor for students.

“For your kids, this may be their only safe harbor — they eat here, they learn here, they probably have more social interaction here than they do lots of times at home,” Walker said. But how can schools facilitate that?

It is essential to redefine safety and wellness, as it is about more than just the hardening of schools. Safety and wellness are about creating social, emotional, intellectual, and physical safety for students and staff from the inside out.

“Your safety and security is kind of like your sewers. You want them to work, but you can’t always see them.”

“Safety” Comes in Multiple Forms

Aside from physical safety, kids need social and emotional safety. They also need intellectual safety so they are comfortable with things like challenging lessons and expressing another view from the standard way of thinking.

Walker also discussed the importance of having restorative physical space, using the following principles:

- Realize how the physical environment affects an individual's sense of identity, worth, dignity, and empowerment.

- Recognize that the physical environment has an impact on attitude and behavior and that there is a strong link between our physiological state, our emotional state, and the physical environment.

- Respond by designing and maintaining supportive and healing environments for residents who've known or who face trauma.

When you start rethinking classroom design, consider what would encourage interaction. After her schools started making changes, the student conversation rate went from 10% to 48% in student on-topic behavior. Why? Giving students more options on things like seating and ergonomics promotes ownership of their learning experience.

“We’ve got to let students have some choice and voice,” said Walker.

Spatial layout plays an important role. Sometimes it’s best to have students in rows for things such as tests. But sometimes they need social space. Their workspace should also be flexible for working in groups of different sizes.

In addition to the traditional principles like being able to see the board, other considerations for spatial layout should include:

- Sit in each chair and/or workspace in your classroom. Do you feel part of the group? Do you have proximity to peers and resources?

- Position students so they do not have their backs to the door, which is especially important for students who have experienced trauma — they will be in a constant state of high alert if their back is to the door.

Strategies for Prosocial Design

The four common design elements of a prosocial learning environment are learning pods, dynamic place, activity zones, and teacher spaces.

“Kids need to move. Kids sitting all day long — just like us, it doesn’t work well. There needs to be some kind of movement,” said Walker.

Students also need some space where they can just relax at times — a place where they can say, “Just give me a minute.”

Walker encouraged the audience to talk to others in different school districts for ideas, but offered suggestions on specific actions each should take:

- Seek resources/training to help better understand the components of a ProSocial Learning Ecosystem™ and how it can impact your district.

- Walk campuses to identify some prosocial components that currently exist and/or any gaps for further conversation.

- Assess your current learning environments and determine one or two immediate actions that could impact student learning.

- Share this information with stakeholders to build on current strengths and strategize to address existing gaps.

Having the Hard Conversations

This approach is an uphill battle, but transparency and having difficult conversations are necessary to make the necessary changes and create schools that truly support the students.

“When we talk about the crisis of confidence, we’re going to have to be transparent, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

“People don’t want to talk about trauma. People don’t want to talk about broken buildings. People don’t want to talk about bad water — they don’t want to talk about negative things,” said Walker.

“When we talk about the crisis of confidence, we’re going to have to be transparent, and there’s nothing wrong with that, but be sure you have data to prove it. Everybody is looking for someone to blame because they’re upset and angry.”

Walker acknowledged that, especially in times of ongoing crises as school districts have been experiencing these last several years, many people working in K-12 facilities management and operations might feel discouraged or that their work goes unnoticed.

“What you do matters,” she told the audience. “A lot of what you do that matters isn’t seen very well. But what you put into these schools and how you build these schools is. Be transparent — be thoughtful and intentional. Find partners that you trust and that trust you and that you mesh with. Because one of the things that happens a lot of the time in education, is in our mind, we have one idea, but our school districts might have another one. Be sure you’re aligned.”

Posted by

Join us at the K12 Facilities Forum!

The community for district and facilities leaders

Nov 8-10, 2026 | San Antonio, TX

Comments