Clarence Carson followed something of an untraditional path to Chief Facilities Officer of Chicago Public Schools (CPS). Though he had a lengthy background in construction and facilities management, his experience in public schools was as PTA treasurer at his daughter’s school – a position she nominated him for.

After he took the volunteer role, Carson found himself proposing and leading efforts to expand three CPS schools. "I did an estimate, I did the schedule, I did a survey of the community, all these different things," he recalled. "Fast forward to May 2018, the mayor came to our school and cut a ribbon.”

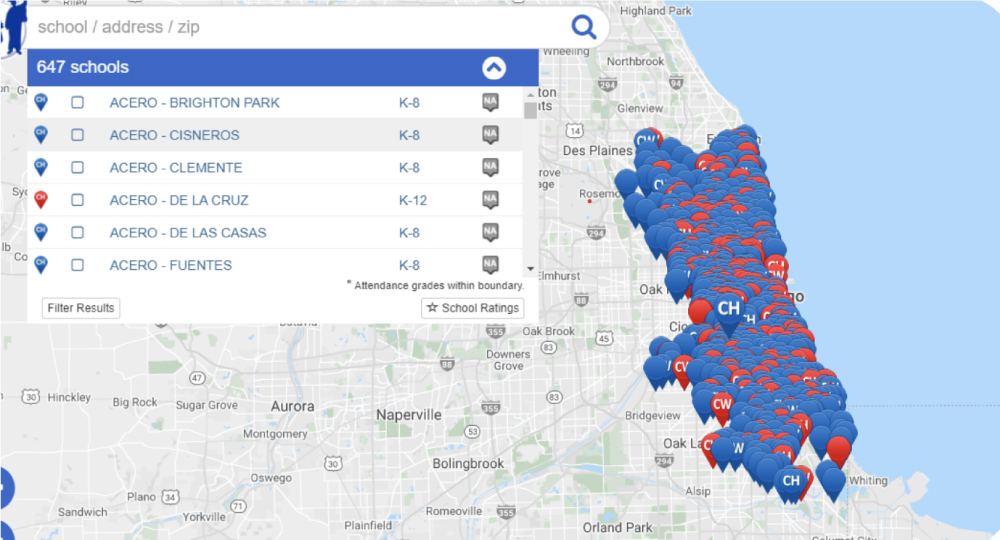

His success pushing for those renovations earned Carson a phone call from CPS’s then-CEO to head up facilities in the school district – the third largest in the country with 600 campuses, 355,000 students, and 50,000 staff. "'We want you to do what you did there for all 600 campuses,’'' he was told. "I couldn't say no.”

As he discovered early in his tenure, which lasted from 2018 until late 2021 (he is now Senior Vice President at DCS Global), CPS’s facilities department was in dire need of an overhaul. The department outsourced pretty much all its operations, giving district leaders very little control over facilities matters in their own schools.

In a recent presentation at the K12 Facilities Forum, Carson explained why he decided to adopt a facilities management office (FMO) model, what it took to make the change, and why he believes other institutions can benefit from an FMO model as well.

“We Were Doing Poorly”

The integrated facilities management (IFM) system Carson inherited was superior to the decentralized model that preceded it, but nonetheless posed its own share of challenges. Outsourcing all maintenance efforts to two IFM companies, the framework gave CPS administrators less control. It reduced individual principals' discretion in managing ineffective (outsourced) staff; provided low visibility into individual vendors' daily duties and sub-vendor contracts; and made it difficult to get new, more diverse vendors in the mix.

As Carson found in his early satisfaction surveys, the district’s principals were less than happy with the status quo. “We were doing poorly,” he said. “Who to call? They didn’t know. Were we responsive? We were not. Did we fix the things they asked us to fix? No. Was the school in a condition they wanted to have it in, during 2017 and ’18 and so on? No. So we had to change.”

The whole system needed an overhaul, and Carson concluded the best route was to abandon the IFM model entirely. By switching over to a facilities management office (FMO) model, he could add needed layers of control within CPS, as opposed to a few officers responsible for a vast web of vendors and sub-vendors.

Placing all CPS schools under a single facilities maintenance program with centralized points of contact, an FMO model would consolidate day-to-day management and oversight within the system. It would also create numerous jobs, from program managers and QA specialists to a director of energy and sustainability.

Stakeholder Engagement

Change takes time, and the IFM-to-FMO overhaul was no exception. Before the transition began, Carson took care to meet with various stakeholders in the school district and in the broader community – principals, school councils, faith leaders, community action councils – both to prepare them for the change and so he could strategize with their needs in mind. "What do you want to see in the facilities department?" he asked them. "Where do we fail? Where do we fall short? How can we improve?" He continued engaging with these stakeholders throughout and after the transition, ensuring everyone was satisfied with the new model.

The FMO framework still heavily relies on vendors, but places them under a more centralized management infrastructure – one where principals actually have a say over facilities efforts in their own schools. A stronger human resources department, meanwhile, allows CPS to respond diligently to performance issues and remain agile in the face of crisis, like a certain big one that hit in 2020.

“With this new model, we brought more custodians into the district – we ended up getting 2,500,” Carson explained. “We staffed up on purpose to meet the challenge of COVID-19. We brought on 100 more building engineers to have less podding in our schools, and more personnel interaction in the buildings to make sure things were repaired more quickly.”

Flexibility and Control

Under the IFM model, CPS had a 1:20 ratio of building managers to schools. Now, it has a ratio of 1:5 – not to mention 625 more building engineers, higher service request turnaround, and happier stakeholders. "It was a way for us to have some flexibility, but also have some control," Carson said of the overhaul. “Have some opportunities to take on new ideas from industry leaders, but at the same time retain knowledge that we had as a district.”

Looking to the future, he said he believes the facilities industry can benefit more broadly from embracing an FMO model, even if there are challenges along the way. “‘The things that hurt us the most can become the fuel and the catalyst to propel us toward our destiny,’” he concluded, quoting Bishop T.D. Jakes. “‘It will either make you bitter or make you better.’ I choose better, and hopefully you all do too.”

Posted by

Join us at the K12 Facilities Forum!

The community for district and facilities leaders

Nov 8-10, 2026 | San Antonio, TX

Comments